KIM COOK

Associated Press

From simple geometric shapes to the intricately wrought details of daily life, the quilt designs in a show now running at the American Folk Art Museum show how powerfully this art form has told stories for centuries and been a vehicle for creativity.

“What That Quilt Knows About Me” comprises 35 quilts and related works in an intimate gallery space.

Some tell stories about the maker’s life or process. Others explore quilting technique, using different materials.

Another quilt in the exhibit is the work of Carl Klewicke, who ran a tailoring business in Corning, New York, in the early 1900s. The piece, made of vivid bits of silk, faille, taffeta and satin, depicts starry constellations, kites and doves – a joyful and precisely crafted celebration of life that took Klewicke 20 years to finish. He and his wife gave it to their daughter on her wedding day.

Sade Ayorinde, one of the curators, says her favorite piece is the Whig Rose and Swag Border Quilt. For decades, it was attributed to a white woman who owned a Kentucky plantation, but an old note pinned to the back reveals the truth: Enslaved women in the household were the real crafters.

Two possible makers have been identified, sisters whose mother cared for the plantation owners’ children.

“It’s incredible to be able to point to the material contributions of Black people in the 19th century as special, valuable and beautiful,” says Ayorinde. “What this quilt knows and exposes is a bit about Black-lived experiences and artistic excellence, even under oppressive circumstances.”

Emelie Gevalt, the museum’s curator of folk art and curatorial chair for collections, was especially drawn to one quilt from West Chester, Pennsylvania.

The “Sacret Bibel” is known by the maker’s phonetically spelled inscription at the top. The name Susan Arrowood is inscribed at the bottom, but nobody knows who Susan might have been, despite extensive research in the area where the quilt was found.

It’s a busy, color- and imagery-packed, appliqued picture book of vignettes drawn from Bible stories, and perhaps from people and experiences in the quilter’s own life.

“Every time I look at it, I find something new,” says Gevalt. “Her composition explodes with creativity. Even though we don’t know much about this quilter, you look at her work and have to imagine that the exuberance of her vision captures something about the maker’s personality and experience.”

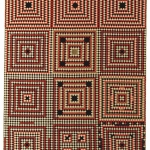

Another powerful piece is the “Soldier’s Quilt: Square Within a Square.” It’s made of the thick red, yellow and black wool used in military uniforms, and curators say the tight geometric motif of small squares was similar to woodworking patterns, perhaps an allusion to an activity considered masculine.

There was a tradition among British soldiers during the Crimean War in the mid-1800s to create quilts as a way to pass the time while awaiting orders or recovering from injuries. The craft was encouraged by leadership as an alternative to gambling and drinking. Imagine weary groups of soldiers piecing and stitching a creative testament to their war-battered years.

Noah’s Ark was a popular theme in late 19th century quilts, and there’s a fine example in the show, from either Nova Scotia or Quebec.

Instead of the usual design, with the ark on top and the animal twosomes parading in a circle around the quilt, this one has the ark in the center, with the couples lined up in rows. Creatures have been scaled playfully; insects are the size of penguins, and cats are bigger than pigs. Another distinctive feature: The quilter included Noah’s whole family.

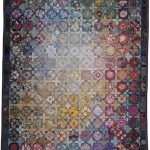

From Tokyo, a quilt gifted to the museum by artist Setsuko Obi is called “Light from Far-Away Space.” Standing a distance away from it gives you the impression of a glowing galaxy surrounded by brightly colored stars. But up close, you see that each block in the quilt is folded like origami, with hand-woven silks and fabrics from antique kimonos.

The exhibition also includes several colorblock quilts that look remarkably modern, including an early 20th century “Diamond in the Square” that’s probably Amish. Amish quilters preferred simple, geometric patterns and colors; the community frowned on overly pictorial motifs and multicolored patterns.

Another stunning yet simple piece is the “Calamanco Quilt with Border,” from the early 1800s. Its wool, made in England using a hot-iron process that created a glazed surface, is dyed two shades of brilliant indigo. Looking at the nearly 8-square-foot quilt gently glowing under the museum’s cleverly unobtrusive lighting is like peering into the depths of the sea.

—-

“What That Quilt Knows About Me” runs at the American Folk Art Museum until Oct. 29.

—-

New York-based writer Kim Cook covers design and decor topics regularly for The AP. Follow her on Instagram at @kimcookhome.